To understand what Archigram is and why it is they produced what they did, one must understand where they came from: the sociocultural environment of the 1960s that brought Archigram’s members together and pushed them to create.

Britain, Archigram’s country of origin, in the years preceding Archigram’s formation, was largely recovering from the second world war, and the sorts of collective trauma and physical carnage it entailed. The war was revealing of the extremes of the modern condition, displaying the destructive potential of social systems and technology through the holocaust and the atom bomb, and thereby deeply influencing popular outlook and modern philosophy. On a more pragmatic level, the baby-boom, housing shortage and economic decline were very apparent in post-war Britain. Due to a policy response to ensuing high demand for housing and education, these were controlled by the state, and thus “by 1948, 40 percent of architects were working for government departments rather than private offices and most others got their work from government commissions as well.” (Beyond Archigram: The Structure of Circulation, Hadas A. Steiner, pp. 42-43). Also, to best approach these issues of high demand, collaborative groups of architects became commonplace.

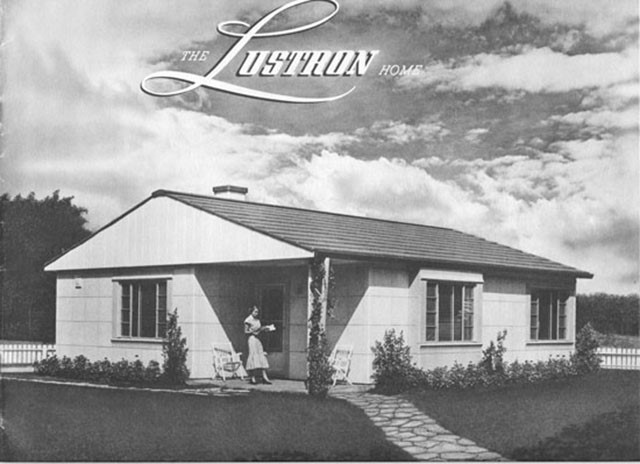

The government’s approach to the housing shortage was to investigate prefabricated and alternative housing strategies, and to promote experiments in the application of new science and technology (which was already present in other consumer-grade industries) to architecture. Scrap aluminum and idle airplane factories were attempted to be reengaged to produce quick and easy housing solutions.

In architectural academic circles, the avant-garde had started to question where modernism would lead after the war. They began to explore regionalist architectures, as was beginning to be done in other countries, and they contemplated what this would mean in the British context. Their answer was to begin considering the British regional, architectural culture as traditionally humanist (versus French rationalism), with a sensitivity to the picturesque, and a focus on having architectural materials reflect faithfully their original, unmanipulated/untreated states and qualities. A new Brutalism was taking hold.

Elsewhere in the world, other very culturally-significant events and avenues of thought were occurring that were having an impact on a global scale. Woodstock and the culture that surrounded it, the equal rights movement and the exploration of the frontiers of space and the world’s oceans were perhaps the most significant, as they implied the strength of counter-cultural movements present at the time (a sign that cultural values and norms were being appreciated as no longer concrete and permanent, a reflection of the culturally subversive, modernist philosophy), and the fascination with the possibilities of technology. Consumerism was also beginning to be criticized, and pop art was gaining popularity.

Back in Britain, Brutalism was starting to be seen as failing in its attempts to achieve its ethical aspirations, and thus invited criticism, criticism which was directed towards all of the modernist movement, “as the demand for flexibility of program increased, along with the sentiment for user participation in and control over the environment.” (Ibid., 1). The avant-garde began to look for new directions in architecture not in the building process, as was the subject of exploration in Brutalism, but rather in digital technology and the potential found in that. The avant-garde sought to change the field of architecture such that “every part of the social experience that was in some way about exchange – of energy, of goods, of services” (54) was incorporated into its focus. Architecture began to move away from static structures designed to accommodate specific programmatic functions, and towards designs that allowed the space to respond to the user’s specific, present needs, and structures that were even temporary and inflatable. The goal of 1960s radical architecture was, philosophically, its own disappearance.

Enter Archigram.

-Tobias